How do you know your business idea is good?

We discussed in our previous article how every company can set up a structured, continuous innovation process and how it can build and sustain an innovation culture. By introducing the Innovation Start-Up Framework (ISF), a four-steps process, companies are well-equipped to unlock the innovation potential across the whole organization.

Everything starts with a good idea. But from a good idea to a validated business there is a long way. A lot of entrepreneurs, and innovators from the established companies alike are tempted to execute ideas prematurely because they seem promising in the spreadsheets and look amazing on PowerPoint 😊

What many innovators forget is the fact that testing means reducing the risk of pursuing ideas that look great on paper but won’t work in reality.

We propose you a three-step process to make sure you do what is needed before you decide to invest in a new business:

1. Formulate your business hypotheses

A hypothesis is an assumption that your business model or your value proposition builds on. It is something that you need to learn about to understand if your business idea might work or not. Hypotheses should be developed to test three main areas: desirability (do the customers want this?), feasibility (can we build this?), and viability (should we do this?). You should first explore desirability, then feasibility and finally you should test the viability of your idea.

Your hypotheses should be testable (you should define the hypotheses in such a way that, after the experiments, they can be shown true or false, based on evidence) and specific (you should know how the “success” looks like in terms of who, what, and when of your assumptions). In order to facilitate the prioritization process, your hypotheses should be kept short and precise, incorporating what you know today.

There is another important aspect: you should formulate them in such a way to avoid the “confirmation bias” trap. What I mean is that if you would always describe your hypotheses in the “We believe that…” or “We assume that…” format, it is likely that you will try to obtain confirmation on what you believe.

Lesson: Don’t forget the fact that your hypotheses should always be testable and specific, so that they allow you to properly de-risk your business ideas. Define your hypotheses with metrics is critical to guide further actions.

2. Prioritize your hypotheses

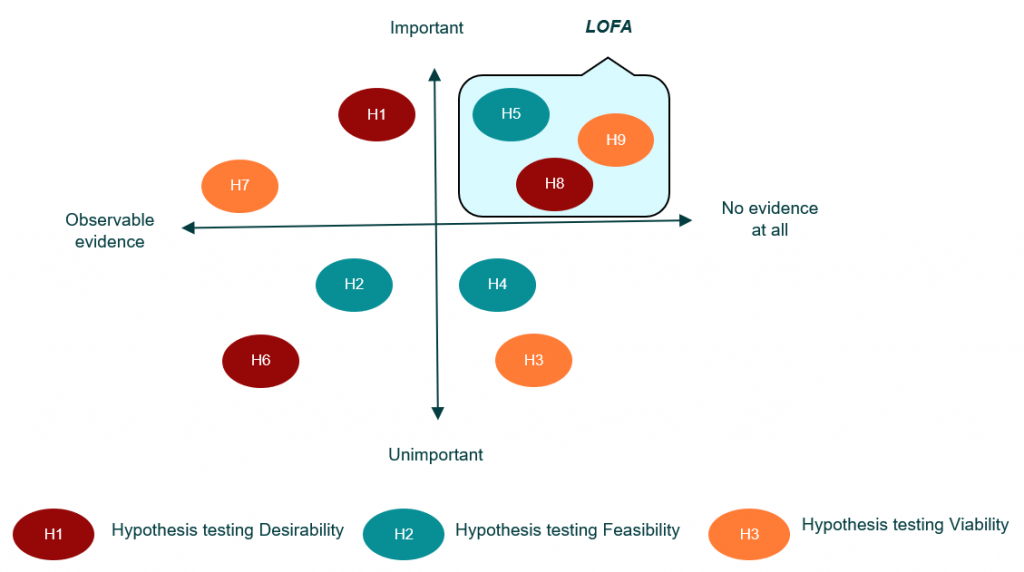

So, at this stage, you will have several hypotheses defined around the three areas previously defined. Now, what you have to do is to prioritize them. For doing that, we recommend using two key elements: the importance of the hypothesis for reducing the risks and the existence of evidence. Hypotheses should be grouped on a 2×2 matrix, as follows:

Once you mapped all your hypotheses, you should start to test them. Testing is really critical, as it means reducing the risk that is associated to your business ideas. The best way in terms of testing is to start with those “important” hypotheses for which you have “little or no evidence”, grouped in the top right of the quadrant. These are called the “Leap Of Faith” assumptions (LOFA): the assumptions that could have the biggest impact on your idea success, and which you are least certain about. If those are wrong, the whole idea has a strong chance to going nowhere.

Regarding the hypotheses in the top left of the quadrant, check them up again: do you really have observable evidence to back them up? You might challenge the evidence in order to make sure it’s good enough. If it is, share the knowledge with the whole team.

Let the “unimportant” tests (on the bottom right) for later. You should do these tests only if you have enough time and resources.

This is a meaningful exercise, as it allows you to think and reflect as a team to de-risk, in terms of biases, what you want to analyze. It also allows you to really prioritize what is the most important thing to test as quickly as possible.

Lesson: Do not execute good business ideas without strong evidence. Start testing the LOFA first. These are the real deal-breaker assumptions that, if invalidated, your business idea needs to be pivoted or changed.

3. Test your hypotheses through experiments. Learn from them

When you test a hypothesis, it is very important that you articulate it in the right way. Let me be more specific with an example:

Testing Desirability

Let’s assume you want to develop a rent-a-bike business and you would like to test if this is a good business idea. You choose the Customer Interview, as a preliminary Discovery experiment. If you start by asking a friend if this is a good idea, you will most probably receive an “oh, that’s a brilliant idea, I’m sure people will love it!”. Is it a good enough evidence? Of course, it is not. But this happens because of the wrong question you asked.

Defining the market segment, you would like to target first, is important, as well. It might be that your business is more suitable for businesses than individuals (B2B instead of B2C). So, instead asking a friend, you might ask a business rep: “did you ever consider renting bikes for your employees?” or “did you consider to offer your employees a convenient last mile solution?” These are questions that offer you valuable feedback about how willing businesses are in using your rent-a-bike solution.

Lesson: Never ask for opinions, people have millions of opinions about everything. Instead, ask for obtaining evidence.

Testing Feasibility

Once you validated the desirability for your product or service, backed by strong evidence, you will need to test the feasibility. You must answer to several key questions, such as: Can we perform all the necessary activities, at the right quality levels? Can we manage all technologies and resources that are required? Can we build the required partnerships to develop our business? What will be the total cost?

Feasibility is extremely critical. Although there is a potential market for us, we have to make sure we can secure and manage all resources, internal and external, to create a sustainable business.

Lesson: Don’t minimize the importance of feasibility just because you acknowledged there is a real need for your product or service. Carefully assess all the necessary resources you need for that.

Testing Viability

Let’s assume now that you want to know how much your customers will pay for your services. Trying to solve the “viability dilemma”, some innovators will be tempted to ask questions such as: “Would you be willing to pay a $50 for a monthly subscription?” You don’t have to ask your potential customers if they are willing to pay a certain amount of money. If they don’t want to pay $50/month, you don’t know why: it could be because they don’t like bikes, or because they don’t like the price, or because they consider biking unsafe etc. First, you should understand the customer’s need, and what exactly using a bike will solve for them. Then, you must have a clear understanding of your costs and what involves that. Only after that, you might ask for a price.

Lesson: Never ask for a price before you understand the customer’s insights (his/her jobs to be done, pains, and gains). Only then you can frame the sale.

Because we sustain innovation and we want to support as many local companies as possible to properly manage innovation, we will continue to share to you, in our next posts, interesting information and best practices from the innovation field. We would be more than pleased to know that at least some pieces of this knowledge have had a meaningful contribution to YOU, either local companies or entrepreneurs. We want these companies to better understand what innovation really means and how they can benefit from its extraordinary advantages.

Our sources of inspiration for this article:

1. David Bland, Alexander Osterwalder – Testing Business Ideas: A field guide for rapid experimentation

2. Tendayi Viki, Dan Toma, Esther Gons – The Corporate Startup: How established companies can develop successful innovation ecosystems

3. Eric Reis – The Startup Way